Contractors Help Hospitals ‘Flip the Switch’ on COVID-19 Rooms

Across the country, sheet metal and air conditioning contractors are assisting health officials and hospitals as they flip the switch on their facilities to deal with surges of local coronavirus cases.

More than a half century ago, a clinic in Albuquerque, N.M., served as the site of medical testing for the first U.S. astronauts. Today, that same facility is playing a far different role as an emergency hospital for COVID-19 patients.

As the coronavirus began spreading across the country in the spring, Albuquerque-based Energy Balance & Integration LLC (EB&I) was tasked with helping retrofit the decommissioned medical building to handle an upturn of positive cases. The challenge: Convert the vacant Gibson Medical Center into a negative pressure environment with 200 beds to isolate patients infected with COVID-19. Essentially, that means configuring air flow in patient rooms so that coronavirus contagions inside the rooms can’t escape.

“You basically have to switch the hospital room 180 degrees from what it was built to do,” says Tony Kocurek, owner of EB&I, which provides testing and balancing services for commercial HVAC systems.

Across the country, sheet metal and air conditioning contractors like EB&I are assisting health officials and hospitals as they flip the switch on their facilities to deal with surges of local coronavirus cases.

Going Old School

Mechanical and industrial construction firm Murphy Co. has worked with some of the major health systems in the St. Louis area this year to address coronavirus challenges. Dan Leath, an institutional HVAC manager at Murphy, describes the process as “old school design on the fly.”

Yet, with a highly infectious disease like COVID-19, hospitals are actually trying to do the opposite — keep the air inside an isolation room from seeping into surrounding areas. To do so, exhaust helps draw air into the room from the hallway and ventilation systems and push the air from the patient rooms out into the atmosphere. The air particles circulating in the room are then expelled out so they can’t escape into adjoining rooms and hallways.Leath notes that the design principles mirror standard isolation rooms in medical buildings. Typically, hospitals design isolation rooms to protect patients with compromised immunity systems. The rooms are therefore “positively pressurized” with higher air pressure than surrounding areas — the better to push outside air flow away from the rooms. That limits the potential for contagions, such as the flu virus, or MRSA, to enter the rooms and infect the occupants.

“This negative ventilation helps draw the air in and take it out of the space to protect everyone outside that specific room where that patient happens to be. You don’t further spread the virus by recycling the air and blowing it into the room next door,” explains Matthew Sano, president of Fisher Balancing Co., based in Williamstown, New Jersey. Fisher Balancing is working with health systems around the Philadelphia area to adjust their HVAC systems to deal with COVID-19 patients.

Gibson Medical Center maximized the number of negative air pressure rooms with EB&I’s help.

Finally, air from inside the isolation room may go through a dilution process before blowing out into the atmosphere. Alternatively, a filtration system might trap the air particles to be treated as hazardous waste.

Shifting Scale

Contractors are finding that projects to COVID-proof hospitals come in all shapes and sizes. Some like EB&I’s project in Albuquerque involve spaces for hundreds of patient beds. In other cases, contractors are assisting with planning for potential outbreaks.

For example, Alliant Systems, based in Portland, Oregon, is advising Skyline Medical Center, a critical access hospital with 25 patient beds in White Salmon, Washington. According to Alliant founder Chris Miller, hospital administrators were looking for solutions that enable them to switch over a portion of their rooms quickly. “The hospital is trying to figure out a way to create a negative environment in those rooms in case they need to put COVID-19 patients there,” he says.

Alliant created a small, single-duct passage through the exterior of the hospital building. In the event of a coronavirus case, the hospital can install a machine in the patient’s room to create a negative pressure environment by hooking a flexible duct up to the wall passage.

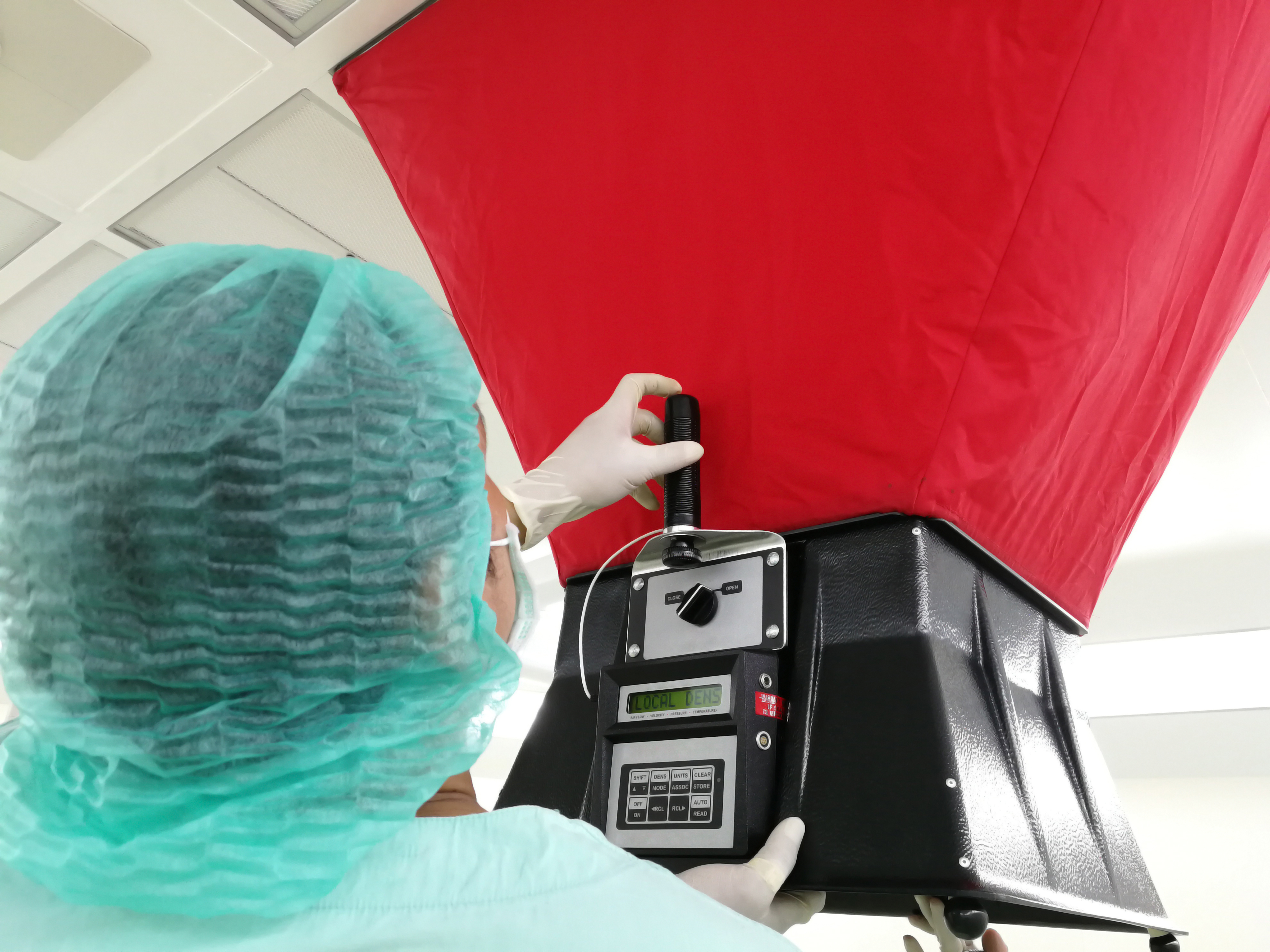

Fisher Balance employee Dane Gresko uses Evergreen Telemetry equipment to establish and read proper airflow in areas with high ceiling installation.

“It’s not a permanently installed solution, but it’s for a small, critical access hospital that has very limited funding,” Miller says. “It seems like that approach fit the bill pretty well for its needs.”

Flipping Back

Of course, while contractors are working now to design medical facilities to deal with the coronavirus, the day will inevitably come when the pandemic subsides. In fact, hospital systems and contractors are already contemplating what it will look like to flip negative pressure rooms back to regular air flow systems.

Not surprisingly, Sano says newer HVAC systems are better suited to switching back and forth between negative and positive pressure. Older systems require more physical manipulation of their equipment.

“On the older systems, you’re doing more physical things like getting up into the ceiling and moving dampers to move that air around,” Sano says. “You don’t have the sophisticated controls at your disposal.”

One natural area of concern will be the condition of the ductwork. “Now you’ve got the potential that whatever virus might be in the rooms or the air stream is in the ducts,” Leath says.

According to Leath, indications are that the coronavirus can remain viable on galvanized sheet metal for multiple days. “Out of an abundance of caution, hospitals may want to consider going through and doing a thorough cleaning of their ductwork, before returning to recirculation.”

Otherwise, the scale of the project will likely play a big part in determining what issues pop up when hospitals start converting rooms back to positive pressure. If a hospital converted a handful of rooms to COVID-19 isolation units, Kocurek says he expects a frictionless transition back to their normal status. “That’s a simple change because you readjust the air flows so that instead of more exhaust than supply, you have more supply than exhaust in the rooms,” he says.

Flipping over a project like EB&I’s retrofit of the Gibson Medical Center, on the other hand, would take more effort and resources.

“There were huge mechanical changes that were made. An exhaust duct was taken out. Air-handling systems were changed to go to 100% outside air going into these rooms,” Kocurek says. “Hospitals have to decide if they want to pay to convert that back.”

Alliant Systems »

Energy Balance & Integration »

Fisher Balancing »

Murphy Company »

Published: August 31, 2020

IN THIS ISSUE

2020 Safety Innovation Award Highlights Pride of Workers

This year’s SMACNA Safety Innovation Award went to UMC for their pride-based safety program that encourages staff to “do the right thing at the right time for the right reasons.”

Capitol Hill Update: Pensions Relief, COVID Deal Stalls, GA Outdoors Act, School Retrofits

The Senate and the House left Washington without agreement on a new COVID relief bill. The stalemate is not good news for SMACNA pension efforts.

Code Inspections Amid COVID-19

For building inspectors, the novel coronavirus has made many of them rethink the way they approach building certifications, and even the way they interact with people on the jobsite.

Contractor Goes Big with Air Force Corrosion Control Facility Upgrade

Matherly Mechanical’s facilities upgrade at Tinker Air Force Base is big on numbers. Read on for some of the notable ones.

Contractors Help Hospitals ‘Flip the Switch’ on COVID-19 Rooms

Across the country, sheet metal and air conditioning contractors are assisting health officials and hospitals as they flip the switch on their facilities to deal with surges of local coronavirus cases.

Employee Stock Ownership Plans Come with Both Risks and Rewards

Maybe you’re thinking that your business is not valuable to a third-party buyer. Maybe you don’t want to deal with the sales process, or perhaps you don’t have the next generation to pass it to. So, what are your options?

Finding Balance Between “Me” and “We”

Whether you are talking about your company’s engagement on a prestigious megaproject or a lone service tech making a routine call, all of us have to manage the tension between individual recognition and collective success.

HVAC Customers Seek Improved Indoor Air Quality

Across the United States, residential contractors have seen an increase in business as clients adjust to the COVID-19 pandemic.

President's Column: Part of the Solution or Part of the Problem

No matter where you fall on the political spectrum, I would hope that you can agree that everyone — no matter their gender, race, sexual orientation, or other distinguishing characteristic — deserves equal opportunity.

Scott Barr Joins SMACNA Technical Group as Senior Project Manager

Scott Barr, the new senior project manager with the Technical Resources Department, joined SMACNA in July 2020.

SEA Airport North Satellite Modernization

The North Satellite (NSAT) Modernization Project combines leading-edge engineering with natural motifs to create a high-tech space with a biophilic design — one that appeals to people’s innate love of nature.

The SMACNA Edge Conference Provides Unmatched Education at an Exceptional Value

This fully virtual event will provide attendees with a truly memorable learning experience that includes presentations on current economic data and forecasts, technical trends, project management, leadership, and other pressing challenges facing you

The Tech Has Arrived. Your Move, Contractors.

Disruptions in supply chains, new safety protocols, remote work, and major project shifts have forced SMACNA contractors to improvise, adapt, and overcome in remarkable ways.

Welcome New SMACNA Members

Welcome New SMACNA Members